Disease-prevention stratigies in calves using non-antibiotics

Antibiotic resistant pathogenic bacteria (superbugs), currently responsible for 700,000 deaths a year, could kill more people than cancer by 2050 at a cost of £63 trillion to the global economy, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) – the ability of microorganisms to resist antimicrobial treatments – has a direct impact on human and animal health and carries a heavy economic burden due to higher costs of treatments and reduced productivity caused by sickness. AMR is responsible for an estimated 35,000 deaths per year in the EU. It is also estimated that AMR costs the EU €1.5bn per year in healthcare costs and productivity losses.

According to WHO projections, the number of cases of resistance is expected to double in more than ten years. By 2050, the number of cases will be four times more than today. The ‘post-antibiotic’ era is near, according to reports released by the WHO. The decreasing effectiveness of antibiotics and other antimicrobial agents is a global problem, with the looming threat that some bacteria may become fully resistant to antibiotics.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) expects a 45 per cent rise in the demand for animal proteins by 2050 and the world must face the double challenge of meeting demands for cheap animal proteins while reducing the risks of AMR. The answer lies not in the increased use of antibiotics but rather in the replacement of them with suitable safe and effective alternatives.

Such a solution can be found by using evidence-based, proven probiotics – only products approved and authorised by a regulatory authority such as the Health Products Regulatory Authority (HPRA) and the Veterinary Medicines Directorate (VMD). The prophylactic use of effective probiotics from birth has been demonstrated under field conditions to enhance gut health, reduce infection rates, and enhance digestion and growth, while amplifying the immune status of the animal.

Reducing the need for antibiotics

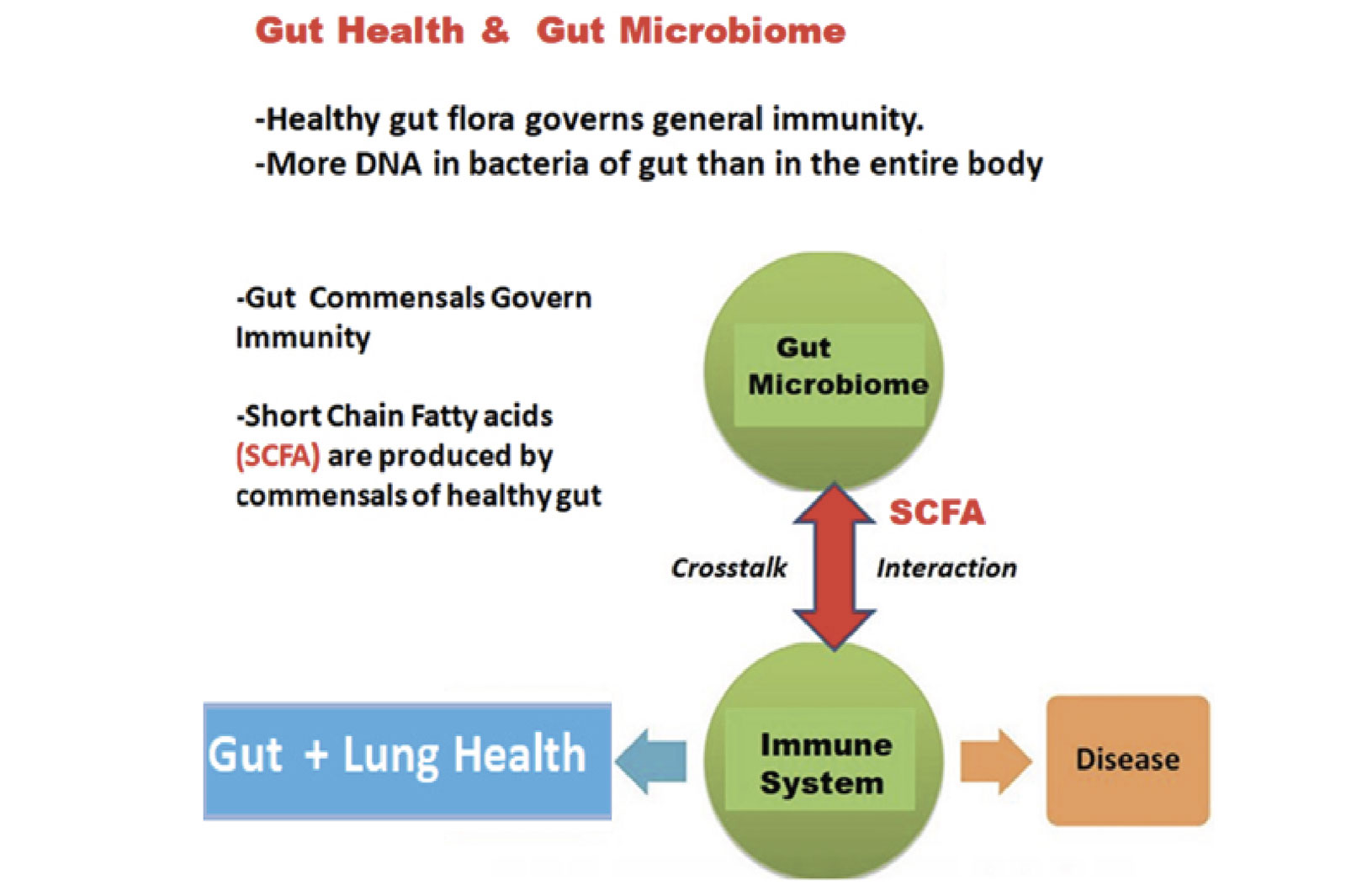

The gut contains billions of organisms (the gut microbiome) and is now known to be the biggest immune organ in the body. A healthy gut microbiome and a healthy immune system will reduce the risk of infectious disease and, therefore, curb the reliance on antibiotics. Antibiotics can be regarded as having a subtractive gut effect, insofar as they strip not only pathogens but also useful immunostimulant commensals from the gut. AMR is also a huge risk with repeated oral antibiotic usage. Probiotics on the other hand have an additive effect on the gut, by seeding beneficial organisms (commensals) which competitively excluding pathogens from establishing in the gut, and also act by stimulating the body’s immune system.

Much American research on rearing pre-weaning calves has shown that early antibiotic usage actually lowers the animal’s immunity, and that calves treated with antibiotics pre-weaning have lowered milk production and reduced productivity as adults.

Neonatal gut and immunity

In neonates, the gut microbiome is underdeveloped, and so it is no coincidence than neonatal animals and human infants are immunologically vulnerable and are most susceptible to diseases immediately after birth. The gut is sterile in utero and becomes populated gradually after birth. It is now well established that a clear immunological link exists between the gut microbiota, the immune system and the presence or absence of neonatal disease.

Several seminal studies in neonatal germ-free animals have unambiguously demonstrated that the absence of microbial colonisation in the neonatal gut results in sub-optimal immune functioning, altered gut epithelialisation, poorer growth, and more frequent disease occurrence. Thus, the gut microbiome and the immune system are connected.

The gut microbiome consists of a population of billions of commensal organisms (good bugs) which provide many beneficial effects for the body, and in fact the gastrointestinal tract is now known to be the largest immune system of the body. This gut microbiota contain more cells than the entire number of somatic cells in the body and this repository of gut-derived DNA is now established as the principal driver of immune health in the newborn. Augmenting this gut microbiome with probiotic organisms at birth is one way to enhance the gut commensal population which upregulates the immune status and thus helps to prevent Escherichia coli infection.

Use probiotics prophylactically

Although the gut microbiome and the immune system are intimately connected, this dual system can only be effectively utilised if probiotics are given prophylactically to all young animals immediately after birth – a pre-emptive strike, in other words. A neonatal gut microbiome infused with early commensal-rich probiotics has been shown to reduce the subsequent incidence of scour and respiratory disease and to propel the young animal immediately up to a higher level of better health and productivity. Waiting for disease to occur and then endeavouring to deal with it by therapeutic firefighting is a waste of time, money, and the animal’s health and long-term productivity. Antibiotics will always be needed and will always be necessary to treat serious outbreaks of clinical infectious diseases. What is at stake here is reducing the frequency of their usage, and indeed, if possible, to prophylactically head off outbreaks of disease before they establish. The usefulness of any antibiotic is inversely proportional to the frequency of its usage. The regular application of oral broad-spectrum antibiotics is a particular problem insofar as it is a very blunt instrument, which affects not only gut pathogens, but also the resident population of beneficial commensals.

Some effects of probiotics

Maintain normal intestinal microflora by competitive exclusion and antagonism to pathogens.

Stimulate the immune system and provide gut immunity.

Improve feed intake and enhance digestion.

Seal tight junctions of the gut.

Provide gut immunity.

Release bacteriocins and immunomodulators.

Immunological 'cross-talk' from gut to lungs

Medical research has demonstrated the beneficial effects of quality probiotics on commensals of the gut, which result in an augmentation of the signalling from the gut microorganisms to the immune system via short chain fatty acids (SCFA) and other signalling inducers. Cross-talk exists between the gut and the lung in terms of the amplified gut microbiome facilitating not just local immunity in the gut but also protection in the respiratory system, the brain and other tissues.

The lungs, in particular, show higher levels of antibodies and immunoglobulin A (IgA) following probiotic administration and respiratory disease has been shown to be reduced following gut probiotic administration. Response to flu vaccine in human patients has been shown to be improved by concurrent probiotic administration.

In other words, disorders, and imbalance in the gut microbiome (dysbiosis) adversely affects not only the gut defences but also the immunological defences in the lungs. Eubiosis in the gut (i.e., a healthy gut flora) is associated with high SCFA whereas dysbiosis in the gut (pathogenic organisms) is associated with a decrease in SCFA.

Results from field trials with a proven probiotic

In field trials with one proven and authorised probiotic, not only was calf scour reduced by 80 per cent, but respiratory disease incidence was also reduced by up to 70 per cent. This is a significant extra beneficial effect. This product also showed a 10 per cent increased weight gain achieved to weaning, a 33 per cent increase in average daily gain (ADG), and a reduction in respiratory disease incidence of 70 per cent. In animals, it is established that calves that have had scour, are approximately 20 times more likely to develop respiratory disease problems.

In human medicine, it has been repeatedly established that a dysfunctional gut microbiome (dysbiosis) is associated with respiratory problems. This is evidenced by the fact that when gut disorders such as irritable bowel disease (IBD), or coeliac disease exist in humans, they are commonly associated with a higher incidence of respiratory infections and related asthma-like conditions.

Probiotic actions

In recent years, some very significant advances have been made in elucidating, with more precision, on the scientific mechanism of action of probiotics with respect to their interactions with the gut microbiome and on the development of immunity in the gut barrier itself. Probiotics contain Lactobacilli and Enterococcus microbial species which have the following beneficial effects within the gut by enhancing the local commensal population:

(1) Crowding out pathogens, blocking E. coli adhesion, and neutralising pathogenic toxins (competitive inhibition);

(2) Influences on the gut barrier itself, including sealing of tight junctions, increasing trans epithelial electrical resistance (TEER), prevention of leaky gut syndrome, stimulation of local gut immunity and the release of natural anti-microbial substances such as, bacteriocins and more;

(3) Immunological effects by the release of chemical signalling agents from the commensal organisms, leading to heightened immunity in the gut mucosal barrier, and in other organs such as the lungs. This immunological potential of probiotics has now come centre stage and has become a primary focus of attention. In addition, peer reviewed papers have clearly demonstrated the positive interaction between probiotics and the gut microbiome and the gut mucosa, in terms of gut barrier protection, sealing of tight junctions, and immunostimulant. Tight junctions are a critical structure in restricting trans-epithelial permeability of pathogens. Chemical signals sent from the microbiota, e.g., via SCFA, such as butyrate, promote fortification of the epithelial barrier through upregulation and sealing of tight junctions, receptor binding to various ligands, and associated cytoskeletal protein. Many scientific publications have shown that in various species, both Lactobacillus acidophilus and Enterococcus faecium (microbial components of probiotics) can seal the tight junctions of the gut, thereby restricting pathogen entry.

(4) It has recently been postulated that probiotic organisms can enhance the response to certain vaccines and may enhance the titer level of antibodies obtained post-vaccination. This is an exciting new area of study. It has also been shown that colostral antibodies and probiotics have synergistic action and provide a solid defence wall in the newborn.

Summary

Judicious use of probiotics from birth can undoubtedly help to populate the young gut with beneficial bacteria, which can then confer numerous health benefits on the neonate: gut health, gut stability, and higher immunity. The probiotic, in short, helps the animal to help itself. These microbial compounds are not therapeutic agents, but rather they act as prophylactic agents to seed the gut, when given to all calves shortly after birth. Apart from improving digestion and growth rates, they also reduce incidence of disease and, thereby, lower the need to have recourse to antibiotic usage.