Helping your herd breath easy this Autumn

Respiratory disease, or pneumonia as it is more commonly known, is a significant cost to dairy farmers. What farmers may not realise is that pneumonia becomes a problem from a young age. Calves that suffer repeated and/or severe bouts of pneumonia may end up stunted for life. Such calves may appear healthy after the signs resolve but do not achieve the same growth rates as their healthy comrades. Research shows that calves that get pneumonia during the first two months of life, are 15 days older at their first calving and also have lower milk yields (during their first lactation) of 525kg in a 305-day lactation. The cause of this poor performance is permanent lung damage and pleurisy from pneumonia.

Multifactorial

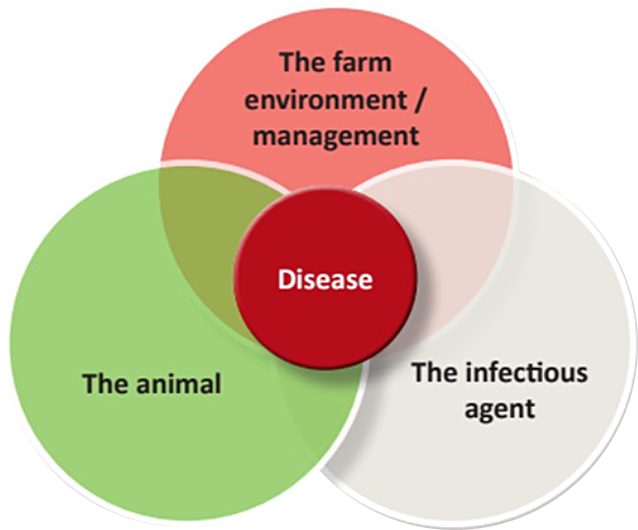

Pneumonia is a complex problem and is often referred to as being a ‘multifactorial disease’. This means that besides infectious agents, a number of environmental and management factors, and their interactions, will determine the occurrence and severity of disease (Figure 1). Cattle succumb when the disease pressure overcomes their immune system. There is no single factor that will control pneumonia and an appreciation of the animal-pathogen-environmental interactions is key to understanding the success or failure of control strategies. Managing just one of these issues will not prevent or control pneumonia – they must be tackled together.

Infectious diseases – the influences

Infectious agents are the small organisms (mainly bacteria, viruses and parasites) that are capable of causing an animal to become sick. However, infectious agents don’t necessarily cause an animal to become obviously ill, and they can often be found in and around healthy animals.

Not all animals will get sick when exposed to an infectious agent. The outcome will depend on the balance between the severity of the challenge by the infectious agent and the status of the animal’s immune system.

The environment influences both the animal and the infectious agents. For example, damp conditions can favour survival of some infectious agents as well as affecting animal behaviour and forage quality, which all contribute to the risk of pneumonia. In some situations, infectious agents can build up in the farm environment to such high levels that the immune system can be overwhelmed (even when it is not compromised).

Figure 1: The most important influences on infectious diseases.

Environmental factors that affect incidence of pneumonia include poor air quality, draughts, humidity and high population density, with the risk of respiratory disease increasing with crowding and mixing of age groups. Any building that contains animals of significantly different ages or that is continuously stocked creates a significant increase in the risk of an outbreak of pneumonia within that building.

Infectious agents and clinical signs

Initial signs of pneumonia can be non-specific and include being off form, dullness, reduced feed intake and lack of gut fill. Other signs may include fever (over 39.5°C), increased respiratory rate, coughing, watery nasal discharge, and severe breathing difficulties. Early diagnosis is crucial because, by the time these later signs are noted, the disease is advanced and treatment is less likely to be successful as damage to the lungs may be irreversible. If you suspect pneumonia, consult your veterinary practitioner for advice on diagnosis and treatment.

The viruses that most commonly cause pneumonia are bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV), parainfluenza virus 3 (PI3V), and bovine herpesvirus 1 (BoHV-1), which causes infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR). BRSV and PI3V are more commonly a problem in calves and young stock. Not all infected animals show obvious signs of disease (sub-clinical infection) but may still experience reduced growth and production.

IBR is a particular challenge because once an animal becomes infected, it becomes a carrier for life despite developing immunity. The virus establishes a lifelong latent infection in the nerve cells within the animal’s brain. At times of stress such as transport, calving, nutritional stress, mixing stock, etc., the virus may be reactivated and can be re-excreted leading to new infection in other susceptible cattle, which in turn will also become latent carriers. Herds with positive bulk tank milk results are considered to typically have at least 15 per cent of milking cows that are carriers.

Bacteria

The bacteria involved in pneumonia include Mycoplasma bovis, Pasteurella multocida, Mannheimia haemolytica and Histophilus somni. Bacterial infection often follows a viral infection, and can cause severe damage to the lung tissue if left untreated or if treatment is started too late. Mycoplasma bovis can cause pneumonia in both adult cows and in calves from a young age to older weaned calves. Diagnosis is difficult without lung samples, taken from either a lung wash or post-mortem.

Mycoplasma bovis is most likely to be introduced by an infected, carrier animal, so good biosecurity is essential to protect your herd. Where Mycoplasma bovis is already present in a herd, many of the general principles of infectious disease control apply.

The following measures will help control spread of infection:

- Ensuring adequate ventilation of sheds where animals are housed;

- Cleaning and disinfection of the sheds and feeding equipment;

- Not feeding colostrum from affected cows;

- Not feeding infected waste milk; and

- Regularly observing animals with emphasis on early detection of infection

Reducing concurrent stressors e.g. overcrowding and mixing animals of different age groups, as well as addressing other potential causes of immunosuppression e.g. presence of concurrent disease, is also important. Isolation of infected animals (housing them away from the rest of the herd, in a separate airspace and, where relevant, milking them last), will help break the infection cycle.

The role of vaccination

Currently, vaccines are available to protect against many infectious causes including, BoHV-1, BRSV, PI3V, Mannheimia haemolytica and Histophilus somni. Unfortunately, there are no vaccines available for other bacteria such as Pasteurella multocida or Mycoplasma bovis. Vaccines are an extremely useful tool to ensure that the majority of animals become immune to the infectious agent before the risk of a disease outbreak, thereby avoiding the losses associated with animals becoming sick and unproductive. Vaccines take time to provide sufficient protection so ideally farmers should plan to use them well in advance of when their animals need protection. In some instances, vaccination does not prevent infection but decreases the severity of clinical disease if an animal becomes infected and/or decreases shedding of infectious organisms. Vaccination protocols are an essential part of herd health planning and should be developed by the farmer and veterinary practitioner together. The exact programme will differ for each farm, depending on which infectious agents you want to protect against. It is important to remember that vaccination is only one part of disease prevention and cannot compensate for poor management or insufficient attention to biosecurity.

The importance of good biosecurity

Biosecurity is simply a technical term for preventing and controlling diseases. Since many respiratory diseases are spread through the movement and mixing of infected animals, you can reduce their spread and impacts by curtailing the inward movement of animals. Biosecurity has become an essential aspect of farming. With the diversity of management practices and disease profiles found on farms, it is crucial to develop a biosecurity plan that suits your system. This should involve veterinary advice and active participation from farm staff to address the particular risks your herd may face. One of the greatest threats to the health status of an established herd is the introduction of new animals. Additionally, newly introduced susceptible animals can also face potential disease risks when integrated into an existing herd. If you do need to purchase, buy in as few animals, and from as few herds, as possible. The risk of disease being introduced increases with more animals, and more sources.