Ciaran Fitzgerald

Agri-food economist

The only real constant is change

For farmers and food processors alike, regulatory compliance requiring more measurement and verification and, in many instances, even constraining production efficiency, is the underlying reality of modern food production. Cost recovery through better prices is not always a given.

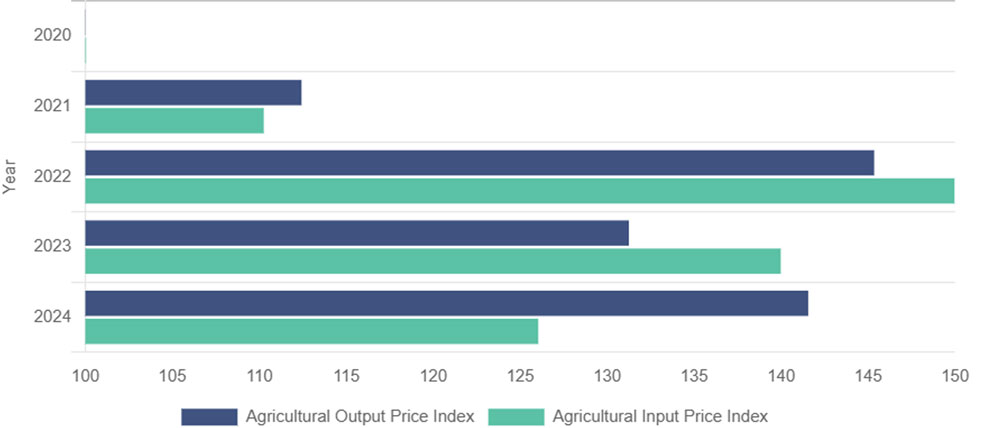

Based on last year’s figures – as per official Central Statistics Office (CSO) data – 2024 was a very good year when compared to 2021 levels, in terms of input and output prices for example (see graph below). Long may this continue to be the case, if Irish farmers are to regain and maintain viability.

Annual agricultural input and output price indices (base 2020 = 100). Source: CSO.

Given the overarching challenge posed by climate change, environmental compliance and sustainability are very much key criteria in bringing food products to market. And, once there, these products are also subject to increased regulation and measurement of emissions reductions, and ever more verification of regulatory compliance.

But cost-competitive everyday low-price requirement in food retail has not gone away and nor has the challenge of delivering on innovation through research and development investment.

Central questions

This reality of ever rising standards and regulatory costs raises the question from farmers, in particular, as to why increased compliance costs should not be automatically rewarded or incentivised, particularly when, as in the Mercosur deal, imported product is not subject to the same compliance/regulatory constraints. Even more fundamentally, both the finance and bandwidth to focus on innovation can get lost in this blur of regulatory constraints and higher cost.

We are fortunate, in Ireland, to have a national food authority in Teagasc that has, for example, through the Marginal Abatement Cost Curve (MACC) delivered many of the solutions required to deliver continuously improving carbon efficiency in our food-production system. Yet, in terms of the ‘green transition’ and broad decarbonisation of food production, we continue to see mostly stick and not enough carrot, particularly when it comes to long-term investment in the agricultural sector.

Competitiveness compass

It is interesting to read the pronouncement by EU president, Ursula von der Leyen, that in a new policy initiative called ‘Competitiveness Compass’ a key factor intended to close the gap between the EU and the US/China in terms of economic growth drivers is to have a more flexible, financially well supported approach to funding/supporting innovation in the EU. President von der Leyen also highlighted a more pragmatic, less bureaucratic approach to regulation across the EU Commission as being an additional factor intended to support EU growth and innovation.

Very clearly, the Irish/EU agri-food sector would cheer to the echo if both ‘softer regulation’ and access to more flexible and competitive finance were to become a reality. But recent history suggests a sceptical wait-and-see approach. In reality, restrictions to financial supports under EU State Aid rules remain a significant obstacle to meeting investment challenges both in R&D and, particularly, in decarbonisation.

Production restraints

This tightness in funding supports is compounded by the new reality, whereby Irish and EU regulation concerning sectoral emissions targets and the Nitrates Directive have effectively 'quota-ised' the livestock sector, which counts for 85 per cent of the value of agricultural output. The December 2024 livestock census demonstrates a continuing decline in beef-cow numbers, down over 300,000 head in the last eight years, while dairy-cow numbers have also declined for the first time since 2009. How does an enterprise absorb very large decarbonisation costs when its output level is capped?

Moreover, the cost of R&D investment is very high and, at food-processing level, comparable to the pharma sector, while the prospects of recovering costs from the food retail market through higher prices has, so far, been minimal if not zero. This is in direct contrast to innovation investment/R&D in the pharma sector which has systematic cost recovery structures.

Drug patent rights and a legal entitlement for manufacturers to set selling prices have ensured a beneficial cycle of investment and cost recovery. New fresh food products or even functional foods do not enjoy such protection, and so costly innovation incurs business risk which is reflected in the cost of finance to the food sector.

Diverse market strategy

The Irish agri-food sector is well embedded in meaningful, measurable sustainability and production practices deriving not least from a reality that 90 per cent of our food and beverage output is exported to 130 countries worldwide.

Very clearly, increased value to the Irish economy – through agri-export growth from €10.5bn in 2014 to €17bn in 2024, and Irish economy expenditure which has seen a similar rate of increase to €18bn in 2024 (CSO) – has been delivered by a commitment to embracing ‘route to market changes’ and adapting to evolving consumer and customer demands, and EU regulations and directives. Nevertheless, in response particularly to IPPC accounting, Irish national policy on emissions reductions, and the challenge of the Nitrates Directive, have constrained and re quota-ised Irish agricultural output. This has the potential to hamstring a sector that supports 220,000 jobs across the Irish economy.

A ‘bespoke’ investment vehicle for Irish agriculture, combined with a 21st century approach to aligning sustainable food production with food pricing, are required to assist particularly in meeting the huge costs associated with decarbonisation of the sector.

Given the overarching challenge posed by climate change, environmental compliance and sustainability are very much key criteria in bringing food products to market. And, once there, these products are also subject to increased regulation and measurement of emissions reductions, and ever more verification of regulatory compliance.

But cost-competitive everyday low-price requirement in food retail has not gone away and nor has the challenge of delivering on innovation through research and development investment.

Central questions

This reality of ever rising standards and regulatory costs raises the question from farmers, in particular, as to why increased compliance costs should not be automatically rewarded or incentivised, particularly when, as in the Mercosur deal, imported product is not subject to the same compliance/regulatory constraints. Even more fundamentally, both the finance and bandwidth to focus on innovation can get lost in this blur of regulatory constraints and higher cost.

We are fortunate, in Ireland, to have a national food authority in Teagasc that has, for example, through the Marginal Abatement Cost Curve (MACC) delivered many of the solutions required to deliver continuously improving carbon efficiency in our food-production system. Yet, in terms of the ‘green transition’ and broad decarbonisation of food production, we continue to see mostly stick and not enough carrot, particularly when it comes to long-term investment in the agricultural sector.

Competitiveness compass

It is interesting to read the pronouncement by EU president, Ursula von der Leyen, that in a new policy initiative called ‘Competitiveness Compass’ a key factor intended to close the gap between the EU and the US/China in terms of economic growth drivers is to have a more flexible, financially well supported approach to funding/supporting innovation in the EU. President von der Leyen also highlighted a more pragmatic, less bureaucratic approach to regulation across the EU Commission as being an additional factor intended to support EU growth and innovation.

Very clearly, the Irish/EU agri-food sector would cheer to the echo if both ‘softer regulation’ and access to more flexible and competitive finance were to become a reality. But recent history suggests a sceptical wait-and-see approach. In reality, restrictions to financial supports under EU State Aid rules remain a significant obstacle to meeting investment challenges both in R&D and, particularly, in decarbonisation.

Production restraints

This tightness in funding supports is compounded by the new reality, whereby Irish and EU regulation concerning sectoral emissions targets and the Nitrates Directive have effectively 'quota-ised' the livestock sector, which counts for 85 per cent of the value of agricultural output. The December 2024 livestock census demonstrates a continuing decline in beef-cow numbers, down over 300,000 head in the last eight years, while dairy-cow numbers have also declined for the first time since 2009. How does an enterprise absorb very large decarbonisation costs when its output level is capped?

Moreover, the cost of R&D investment is very high and, at food-processing level, comparable to the pharma sector, while the prospects of recovering costs from the food retail market through higher prices has, so far, been minimal if not zero. This is in direct contrast to innovation investment/R&D in the pharma sector which has systematic cost recovery structures.

Drug patent rights and a legal entitlement for manufacturers to set selling prices have ensured a beneficial cycle of investment and cost recovery. New fresh food products or even functional foods do not enjoy such protection, and so costly innovation incurs business risk which is reflected in the cost of finance to the food sector.

Diverse market strategy

The Irish agri-food sector is well embedded in meaningful, measurable sustainability and production practices deriving not least from a reality that 90 per cent of our food and beverage output is exported to 130 countries worldwide.

Very clearly, increased value to the Irish economy – through agri-export growth from €10.5bn in 2014 to €17bn in 2024, and Irish economy expenditure which has seen a similar rate of increase to €18bn in 2024 (CSO) – has been delivered by a commitment to embracing ‘route to market changes’ and adapting to evolving consumer and customer demands, and EU regulations and directives. Nevertheless, in response particularly to IPPC accounting, Irish national policy on emissions reductions, and the challenge of the Nitrates Directive, have constrained and re quota-ised Irish agricultural output. This has the potential to hamstring a sector that supports 220,000 jobs across the Irish economy.

A ‘bespoke’ investment vehicle for Irish agriculture, combined with a 21st century approach to aligning sustainable food production with food pricing, are required to assist particularly in meeting the huge costs associated with decarbonisation of the sector.