Ciaran Fitzgerald

Agri-food economist

A missed opportunity?

Beef prices and demand for beef locally and globally are thriving but a systemic shrinking of the national herd means that the Irish beef sector may fail to benefit fully from the improved price profile of the sector. This outcome would reduce the economic contribution of the sector to the Irish economy and, perversely, see global emissions from beef production increase.

Irish livestock profile

Ireland has 67,000 beef farmers, with an additional 12,000 people employed in meat-processing facilities across the country. The Irish beef sector produces just over 650,000 tonnes of beef annually. Exports valued at just over €3.2bn account for 95 per cent of that production, amounting to almost 620,000 tonnes, with the remainder consumed locally. That export tonnage makes Ireland the sixth biggest beef exporter in the world. Moreover, livestock farming and meat and dairy processing in Ireland represent 80 per cent of our national agricultural output with a combined total ex-factory revenue of almost €10bn. However, the beef herd in Ireland has been decimated over the last 10 years with beef suckler cow numbers down by 400,000 head, principally in response to a domestic onslaught that has demanded reductions in livestock numbers, initially in regard to carbon emissions but now also in the context of the Nitrates Directive.

Policies and prejudices

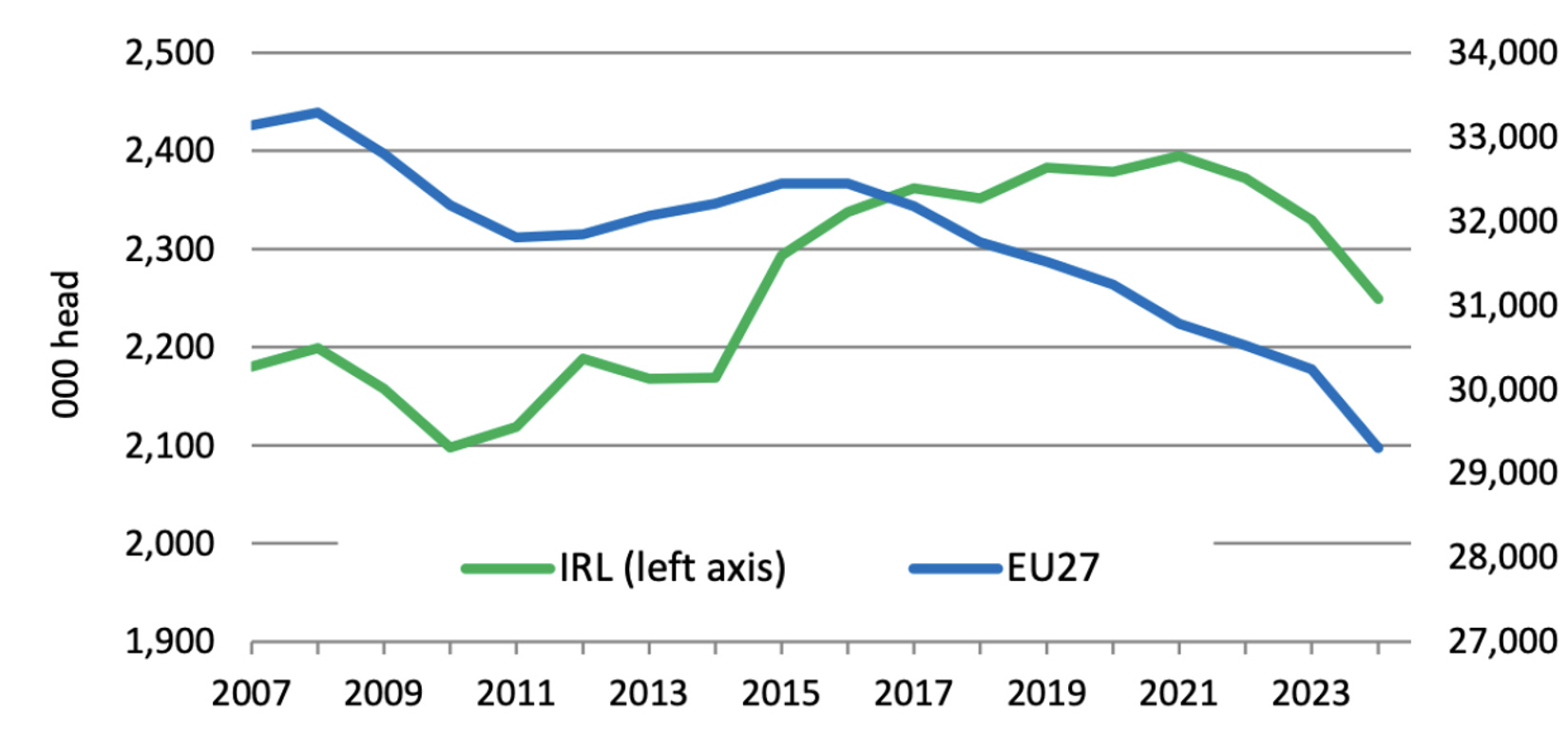

This latest politicisation of regulatory requirements means that livestock numbers, supplies to Irish meat factories and, inevitably, the ability of the beef sector to continue to provide a unique regional and rural contribution to the Irish economy, are being threatened through incessant downward pressure, largely deriving from constraining domestic policies and prejudices. As illustrated in figure 1 and highlighted in greater detail later on in this article, Irish beef cow numbers have declined dramatically with dairy cow numbers now also showing some decline. It should be noted that all of this decline is before any impact from the potential loss of or further reductions accruing from our nitrates derogation.

Figure 1: Irish and EU27 cow inventories December 2007-2024. Source: Eurostat.

Beef farming, unlike milk production, has a multi-enterprise profile both in terms of the origin of animals and the number of stages in the calf to finished beef farming processes.

The 1.8 million average annual meat factory throughput of the last four or five years comes from two sets of breeding stock. Our beef-herd component has declined quite dramatically with beef suckler cow numbers reduced, as previously stated, by over 400,000 head from a decade ago. Meanwhile, the other contributor to Irish beef output, the dairy herd, having grown with the abolition of milk quotas in 2015, has now stabilised.

Moreover, beef cattle may have gone through four to five farming enterprises involving calf to beef, calf rearing, pure beef finishing and all the other intermediary stages that form the rather unique Irish livestock production chain. Importantly all of these farming interactions involve multiple social and economic experiences that are not replaced when livestock numbers decline.

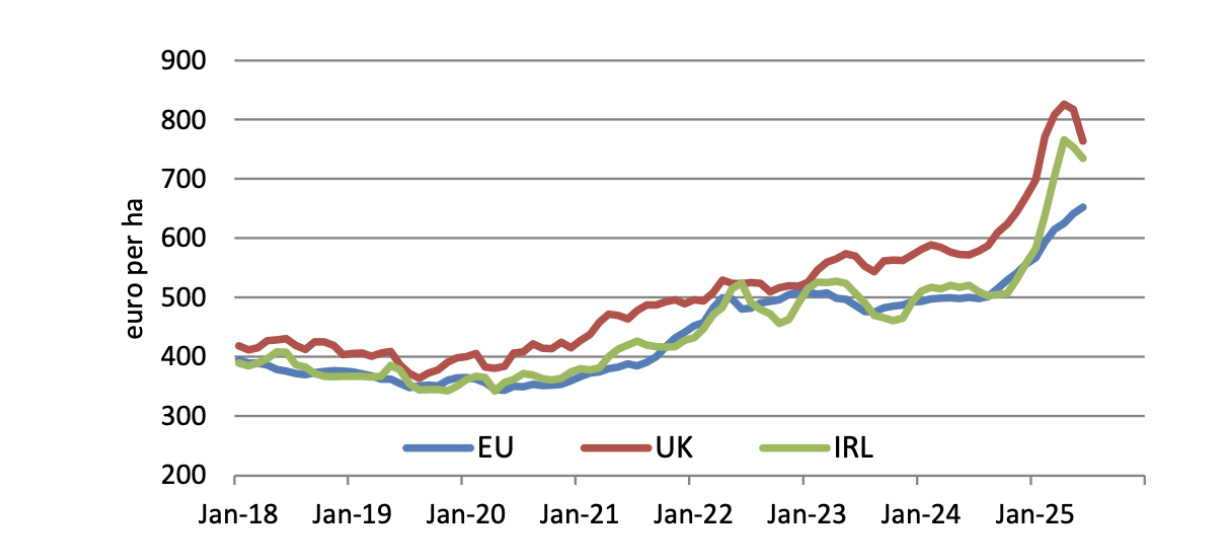

This decrease in cow numbers, especially in the suckler herd, is in contrast to the economic signals from the EU beef market and indeed the global marketplace where demand for Irish grass-fed beef is increasing. Indeed, as shown in figure 2, beef prices to farmers over the last number of years have increased quite substantially.

Figure 2: Monthly EU, UK and Irish finished cattle prices 2018-2025 (excl. VAT). Source: DG Agriculture and Rural Development, AHDB and ECB.

A perverse anomaly

Perversely, the relative importance of agriculture and livestock production across the Irish economy currently and historically has created an emissions management and reduction anomaly. This has allowed what I consider to be, an anti-agriculture prejudice to dominate the public narrative so that reductions in Irish livestock numbers (rather than reductions in livestock emissions) are now entrenched at the core of a national climate action process. Moreover, when this weaponisation of IPCC accounts is challenged, a blunt repost that Ireland signed up for the Paris Agreement of 2006 conveniently ignores and dismisses the very specific statement in Article 2 of the Paris agreement: ‘Increasing the ability to adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change and foster climate resilience and low greenhouse gas emissions development, in a manner that does not threaten food production’.

As confirmed by the December census of 2024, the decline in beef cow numbers is continuing, with a year-on-year fall of 50,000 head by December 2024 versus December 2023. The total loss in beef cow numbers is almost 400,000 head since the peak of 1.16 million suckler cows in 2012, according to the Irish Cattle Breeding Federation.

The great suckler cow exodus

A key element of this reduction in suckler cow numbers is the regional spread, with the chart showing that suckler cow numbers in Connacht, where dairying is not a mainstream of livestock production, have declined by over 100,000 head. There is no real sign, despite better prices for beef cattle along the supply chain, that this rush to exit suckler cow farming has halted in any way, with the 50,000 head reduction in 2023/24 being the highest in recent years. Very clearly, the legal challenges to both the Nitrates Directive and dairy expansion, led by An Taisce, encapsulate this anti-livestock farming lobby view that promotes dramatic reductions in livestock numbers as the sole ‘policy’ solution to any and all environmental challenges.

However an additional part of this bias against the beef sector and Irish agriculture in general derives from a place of ignorance concerning the unique and substantial economic impact of the agriculture sector across the rural and regional Irish economy. This is manifested as indifference to the consequences of a diminished Irish Agriculture sector based on a superficial view that because we have a large multi-national sector we don’t need Irish beef or indeed Irish agricultural activity to any great extent beyond supplying the domestic consumer economy. Even in that context, there is a demand from some environmentalists that Irish farmers redirect their activities from livestock production based on a competitive grass-based system towards plant-based production, in which we have neither the soils, expertise nor scale to compete.

As is well illustrated by the current and very raw experiences of our close neighbours in the UK from Brexit, no good tends to come from economic self-harm.