Ciaran Fitzgerald

Agri-food economist

Long-term Decline in the National Herd

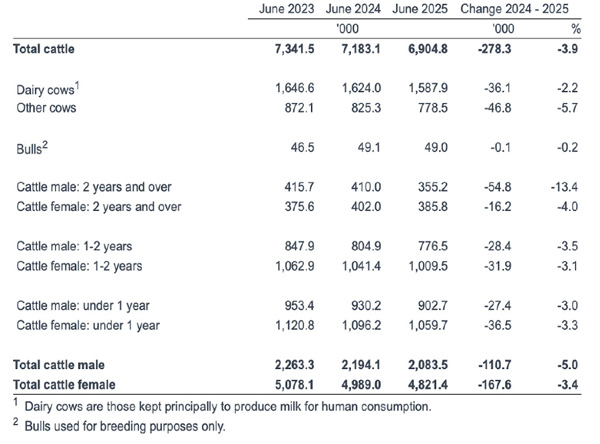

Ireland’s beef cow numbers have been on a sustained downward trajectory for more than a decade. According to the Central Statistics Office (CSO) livestock census in June 2025, the total cattle population fell by 278,300 head (3.9 per cent) to 6.9 million, marking a 12-year low. The decline is most acute in the suckler sector, where numbers fell by 46,800 (-5.7 per cent) between June 2024 and June 2025 alone, continuing a long-term trend. Over the past 10 years, the suckler herd has contracted by around 270,000 cows, and by over 400,000 since its 2012 peak.

Official explanations highlight low profitability, income volatility, and an ageing farmer demographic. However, many within the sector also point to the pressure of carbon reduction targets and increasingly complex environmental verification rules, which have made life more difficult for smaller, traditionally run beef herds.

Fragmented and complex

Unlike dairy, Ireland’s beef industry is not an integrated production model, with the calf-to-beef integrated system accounting for less than 20 per cent of cattle sold for slaughter each year. Instead, the sector comprises a patchwork of systems from autumn- and spring-born steer production to dairy-beef runners, continental weanling systems and bull beef operations. This fragmentation makes it difficult to assess how increases in finished cattle prices translate back to suckler cow margins. Each system responds differently to market signals. When finished cattle prices rise, the benefits often dissipate along the chain. A stronger weanling price might boost suckler margins, but it simultaneously increases input costs for finishers. As a result, price increases rarely trigger uniform incentives across the sector, and that complicates any simple cause-and-effect link between higher beef prices and herd expansion.

Table 1: Total number of cattle. Source: CSO, June Census 2025.

Price versus policy

Over the last half-century, the main drivers of Irish beef cow numbers have been policy supports rather than market prices. After the price collapse of 1974, the beef cow herd fell from about 800,000 head to 400,000 in the 1980s. Recovery only came with the 1992 Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) reforms and the introduction of the suckler cow premium, which pushed the herd above one million by the mid-1990s. The removal of coupled payments and the erosion of direct support levels in more recent CAP reforms have contributed significantly to the ongoing decline.

Turning a corner?

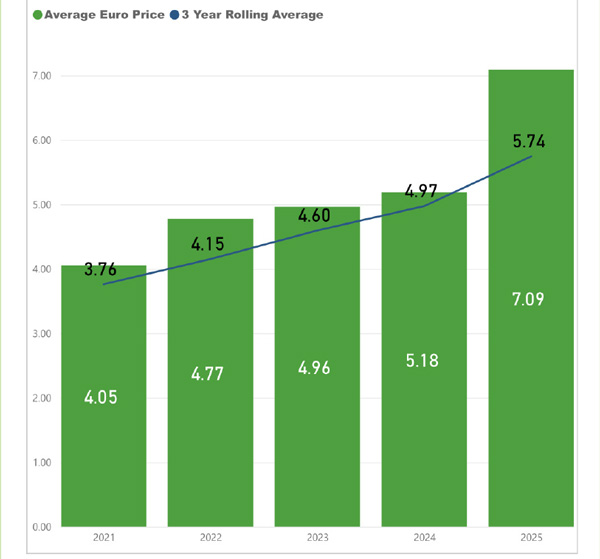

Despite historically low incomes, 2024 marked a turning point. According to Teagasc data, most beef systems recorded positive net margins for the first time in years. Single suckling enterprises moved from a negative €20/ha margin in 2023 to a positive €108/ha margin last year, with a margin of €133/ha or higher predicted for 2025. The drivers of these higher margins include higher cattle prices, along with reduced fixed and variable costs.

Cattle finishing enterprises, too, have seen margin improvements, with this year’s margin expected to hit €191/ha, up 8 per cent on 2024. Meanwhile, dairy-beef systems have come from a 2023 average margin of €162/ha (with the top third achieving €649/ha), to an average margin last year of €402/ha, driven by higher gross output and lower costs. However, performance varied widely, with the top-performing farms reaching €811/ha, while the bottom third averaged €66/ha. However, as mentioned above, despite better margins than other systems, the calf-to-beef integrated model is a minority pursuit on Irish cattle farms.

For general context, Teagasc’s 2022 data showed average family farm incomes of just €9,400 for cattle rearing farms, compared to €18,800 for finishers. That year, higher weanling prices failed to offset rising input costs, underlining how fragile profitability has been.

The recent margin improvements, driven by record beef price, may finally offer some relief. But they raise two crucial questions: will current price levels last and where does suckler beef sit in the environmental and policy agenda? While producer margins are up, sustainability depends on how long today’s exceptional beef prices persist. History suggests that price spikes alone rarely sustain herd rebuilding, especially without policy incentives. Future support will hinge on how suckler systems are valued politically amid climate commitments. Without targeted payments recognising their environmental and rural contribution, price improvements may only slow, not reverse, the decline in numbers.

Table 2: Average annual R3 steer prices with three-year rolling average. Source: European Commission.

Resilience

Despite record prices and reduced supply across Ireland, the UK, and the EU, beef demand has held up surprisingly well. Predicted price elasticity effects, where consumers would switch to cheaper proteins like chicken or pork, have been weaker than expected. This suggests a growing consumer appreciation for grass-fed, low-carbon Irish beef, even amid strong calls for plant-based alternatives.

Profitibility picture

Despite ongoing structural decline, 2024 and 2025 have brought the most encouraging financial outlook for beef producers in many years. According to Teagasc, net margins across nearly all beef systems have improved dramatically, driven by higher cattle prices, reduced input costs, and improved efficiency. The recent turnaround is therefore significant. All major beef systems are forecast to post positive net margins this year, a psychological as well as financial boost for a sector long accustomed to surviving on direct payments rather than market returns.

The Irish beef sector stands at a crossroads. Current prices and margins are the most encouraging in many years and may well apply the brakes to the long-term fall in suckler numbers. However, unless profitability becomes structurally sustainable, supported by coherent policy measures and a stable environmental framework, a full-scale recovery in herd size remains unlikely. The current upswing may mark not a reversal, but a pause in decline and the beginning of a more cautious, sustainability-focused beef era in Ireland.

Conclusion

Ireland’s beef sector has proven its resilience many times before. It has survived price collapses, CAP reforms and shifting consumer preferences. Today, it faces a new challenge: balancing environmental responsibility with economic survival.

Rising prices have offered a glimmer of hope but they are unlikely to trigger a dramatic turnaround on their own. More likely, they will apply the handbrake to the long-term decline, providing breathing space for policymakers, processors, and farmers to rethink how Ireland sustains one of its most iconic agricultural enterprises.

The next few years will reveal whether this moment of profitability marks the start of renewal, or simply a pause in a longer process of structural change.