Ciaran Fitzgerald

Agri-food economist

Addressing the anti-farming narrative

In 2004, a formal Government-initiated review of Irish industrial development policy, entitled Ahead of the Curve concluded that the Irish agri-sector was a sunset industry, and that Ireland Inc. should place all its bets on the ‘modern economy’ sectors like pharma, medical devices and IT. The key metric used by the review process in 2004 for the assessment of contribution/value to the Irish economy was gross value added (GVA). Given the fact that the agri-food sector is a low-margin business and we had had both foot-and-mouth and BSE issues in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Irish agri’s GVA figure was low, at the time. Moreover, the economic commentary at the time declared that modern economy development ‘naturally’ involved the replacement of agriculture with industry, and the subsequent replacement of industry with services and so on – a seamless economic development narrative that fell apart in the great recession from 2009 onwards.

Economic realities

Furthermore, in reality, the GVA contribution of the modern economy sectors, which was dominated by multinationals, while quite large on paper, lost 60 per cent of its value when transfer pricing and profit repatriation was taken into account.

The scary part of this farce was not just that agriculture was dismissed but that the multinational sectors – which were very transparently being incentivised to invest in the Irish economy through our low corporate tax regime – would, as proposed in Ahead of the Curve, be further incentivised by the creation of a €1bn-plus development fund, while the agri-sector would be left to paddle its own canoe. Indeed, only the onset of the economic crash in 2008 killed off the proposed modern economy fund.

The real value of agriculture

My point in raising this issue after the last three years of the anti-agriculture onslaught, is not just to remind ourselves that we have been here before, but to suggest that we, in the agri-food sector, need to find a better metric to articulate the economic value and relevance of the sector. The reality is that, despite many public statements that purport to understand the unreliability of Ireland’s formal gross domestic product (GDP)-based economic accounting figures, we in agriculture have yet to come up with and express a more meaningful metric that captures the true economic impact and underlying value of the broad agri-food sector. I would suggest that this is important, not just in terms of economic sobriety, but also to prevent the shrinking of the agri-sector through ignorance of its true value and, in particular, its unique contribution to the rural and regional economy.

Studies by the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) and National Economic and Social Council (NESC) have highlighted how, even under current economic development patterns, in excess of 60 per cent of all additions to the Irish population could end up on the already-crowded east coast. Constraining Irish agriculture will only further skew regional economic development.

Selling power

Moreover, the point about the GDP distortions is not a defensive one on behalf of agriculture because it doesn’t suit. GVA is, effectively, a measurement of profits and I would suggest that profit levels are a measure of selling power. So, the mobile-phone sector and the pharma sector have selling power and producers of these products set their own retail price. These companies make huge profits and huge GVA.

The agri-food sector, in contrast, is not allowed by law to set retail prices under the resale price maintenance (RPM) regulations introduced in the 1960s.

And, whereas food producers have none or very little selling power, we know that supermarkets and other large retail distributors and discounters have buying power and moreover account for 96 per cent of grocery sales in the Irish market. So, given that GVA understates the value of the agri-sector and overstates the contribution of the multinational sector, an alternative metric is needed. Looking at the Irish agri-food sector from within, the key milestones and barometers of performance over the last number of years could be:

- The exemplary performance through the Covid-19 years 2020-2022 when global restaurant/café and hotel sectors, which constitute 30 per cent-plus of the broad food consumption market, were effectively shut and yet Irish agri-sector exports (which constitute more than 90 per cent of its total Irish meat and dairy production) saw no factory closures or product being dumped, unlike our near neighbours in the UK and elsewhere.

- Growth in the value of gross agricultural output from €6bn to just over €12bn between 2012 and 2022, even though there has been something of a fall off in value in 2023 (CSO).

- Export values – overall exports to around 110 countries when non-food products are included – reached €18.5bn in 2023 (CSO and Bord Bia).

Additionally, the key metric of Irish-economy spend increased to over €17bn annually, with the agri-food sector spend being three times more in the Irish economy than that of any other business sector, including the pharma and medical device sectors (Department of Enterprise, Trade & Employment [DETE]: Annual Business Survey of Economic Impact). As a result, employment – direct and indirect – reached 220,000 jobs across the rural and regional Irish economy in 2022 (CSO).

Surging output

On a more secular, granular level, milk production post quota abolition reached just over 9bn litres, up 70 per cent. Beef exports consistently run at more-than 600,000 tonnes with Ireland the sixth biggest exporter in the world.

At the same time, and in line with environmental and sustainability ambitions, there has been a 360,000-tonne reduction in fertiliser usage in 2022 and 2023 and a 2 per cent reduction in carbon emissions from the sector in 2023 when compared to the 2018 baseline year.

Net and gross export figures

There is plenty of substance in all the above, I would suggest. Clearly, there are occasions when annual reports will highlight some or most of the metrics outlined above but without some additional context, how meaningful are, for instance, export figures?

An annual total value of exports of €18.5bn represents a huge achievement for the agri-food sector, up from €11bn euro in 2016, but the official CSO export figures, which include multinational transfers, would show total annual Irish economy exports valued at €330bn, thereby seeming to diminish the value of agri-food exports.

I have argued in the past that the Irish economy expenditure figures produced annually by Enterprise Ireland, the IDA and DETE are, by far, the most relevant metric of true Irish economy impact, in that they clearly and specifically reflect Irish economy activity as distinct from global transfers, intellectual property or patent registration or accounting adjustments that have low or no real Irish economy impact.

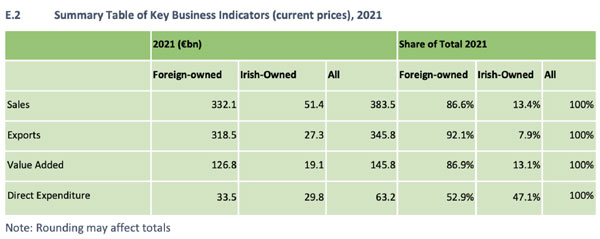

The chart below from a DETE annual report highlights the relevant figures by sector for exports, value added and Irish economy expenditure. This illustrates, I would argue, a much more balanced Irish economy than the distorted GDP figures represent.

And just to be clear, the intent is not in any way to diminish the value of the foreign direct investment (FDI) sector. There is no conflict between having a thriving agri-sector and a thriving FDI sector and a lesson learned, surely, from the blow-up of the Irish economy through the property and banking boom was that we need several economic horses in the broad development race.