Ciaran Fitzgerald

Agri-food economist

Let’s talk true sustainability

Last week saw a clarification by Joe Healy, chair of the board of An Rialálaí Agraibhia, the new agri-food regulator, that it will not be addressing the issue of below-cost selling as part of its remit. No surprise, perhaps, but a critical issue, nevertheless. Below-cost selling/loss leading is a critical challenge to the basic economics of Irish Currently, retailers sell fresh products like liquid milk, cheese and fresh meat and, in particular, fresh fruit and vegetables at low or no margin to attract customer footfall. While the retailer can and does recover margin from the broad range duce supplier does not have that opportunity.

Loss leading is a significant issue for the dairy and meat sectors but the fact that these sectors have huge export markets gives them some leverage against dominant retail buying power. In contrast, the fruit and vegetable sector does not, and loss leading/margin erosion has been a key factor in the huge decline in Irish production of fruit and vegetables over the last thirty years. This failure to align policy on food pricing with aspirations on food production is unfortunately a significant and critical flaw in not just Irish but EU agri-food policy.

What we know

In the absence of joined-up thinking on price and production, the real economics of fruit and vegetable production in Ireland is likely to follow the pattern of recent years.

We know that supermarkets and discount retailers control 96 per cent of the market for fruit and vegetables in Ireland.

We know from these retailers that Irish and other consumers in the EU single market want access to an expanding range of fruit and vegetables on a 52-week basis.

We know that producers in Europe with access to cheap natural gas, like in Holland for example, or with a more benign climate, like in southern Spain or Italy, can deliver a significant part of the 52-week requirement.

We know that global distribution supply chains can and do deliver the remainder on a 52-week basis.

We know that all these producers have lower production costs for the broad range of products demanded than Irish producers.

We also know, critically, that food retailers see fruit and vegetables as loss leaders, i.e. products sold on promotion, used to bring in footfall, and so neither the retailer nor the producer is earning big returns on these products.

We know that the reality of this diminishing margin return has meant that the number of fruit and vegetable producers in Ireland has declined by over 60 per cent in the last 20 years, reflecting the evolving economic reality set out above.

We know that a further consideration in terms of fruit and vegetable production on suitable land on the eastern seaboard has been demand for land for development /house building.

We know that programmes looking at the strategic development of the sector have been produced within the context of the Food Harvest process and while growth is aspired to. Nobody with any real knowledge of the sector thinks that fruit and vegetable production is in anyway likely to replace grass-based food production in Ireland.

Economic reality

At the risk of stating the obvious, the ever shrinking size and profile of the Irish fruit and vegetable sector reflects economic reality, as does the size and profile of the dairy and meat sectors.

And, yet, there is a continuing narrative from environmental lobbyists and wishful thinkers that states that the ever-diminishing production of fruit and vegetables in Ireland represents a blindness to missed opportunity.

This is, in my view, equivalent to suggesting that the German car industry, which is struggling right now, should not focus just on moving from producing diesel cars to electric vehicles but should, instead, start making bicycles, which are clearly more climate friendly.

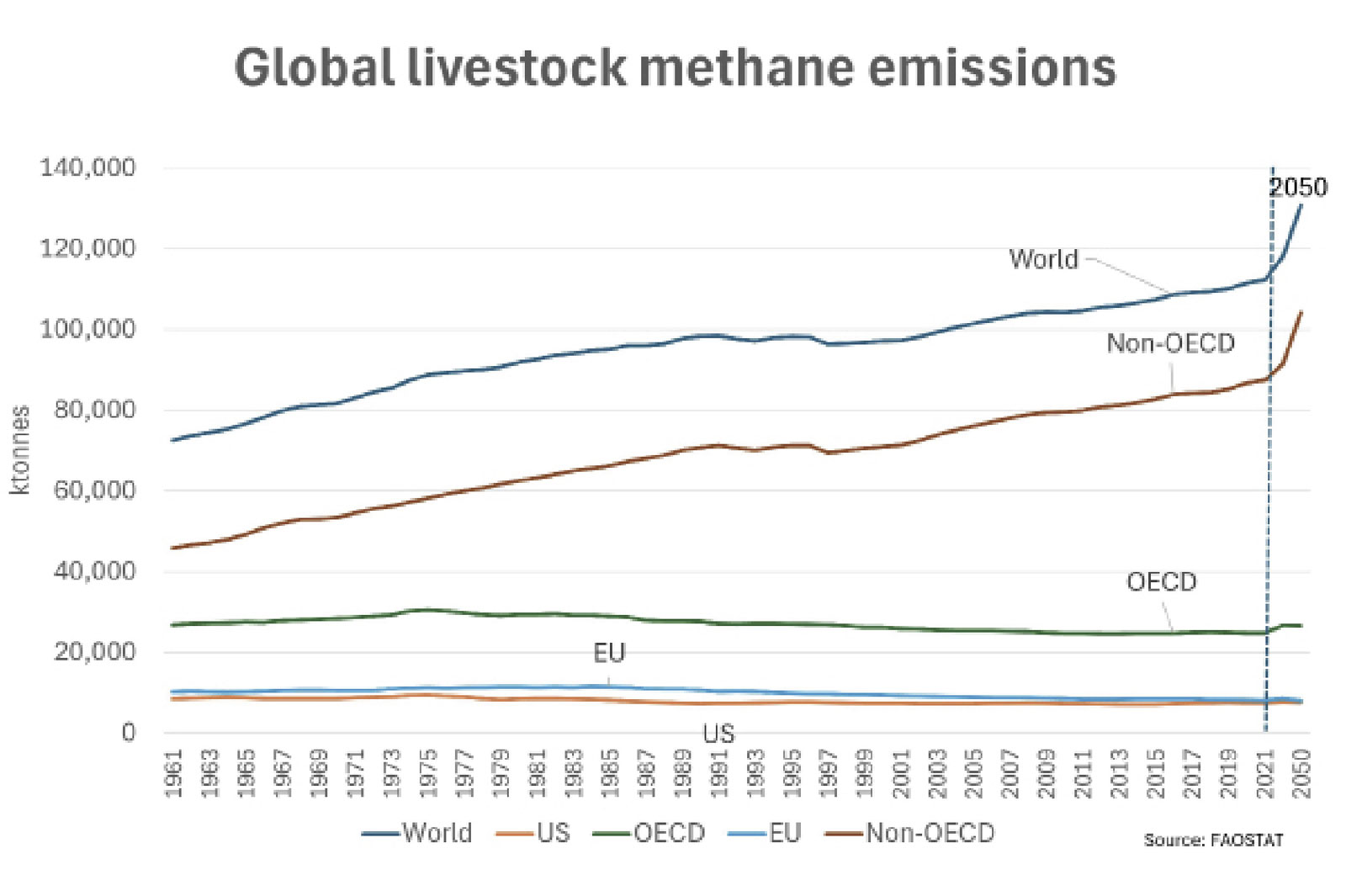

This plant-based obsession does not trump basic economics and is significantly out of sync with the more balanced thinking emanating from the World Food Programme, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and others, and indeed the 2015 Paris Accord on climate change..

Source: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

A global reality

A consistent feature of the global debate on climate action has been a realisation that there are balancing factors to be managed when it comes to meeting the requirements to reduce emissions from agriculture and the need to continue to produce food for a growing global population. Recognising this dilemma, the Paris Accord and the most recent COP 28 emphasise the equal imperative of feeding a global population that is forecast to grow from six billion people to nine billion people by 2050.

Indeed, Article 2 of the Paris Accord specifically commits its signatories (including Ireland) to ‘increasing the ability to adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change and foster climate resilience and low greenhouse gas emissions development’.

The FAO submission to COP 28 talks about intensifying livestock production in ‘relevant locations’. FAO/OECD forecasts out to 2030 show an increase in global demand for meat and dairy currently met from unregulated regions because of restrictions on output in the EU and US. So, in the absence of a more balanced approach, as outlined above, suppression of production in the EU /Ireland will have the perverse effect of increasing global emissions from food production.

Sustainability through specialisation

The Irish Agri food sector has demonstrated a huge competence in absorbing a myriad of shocks and market upheavals over the last thirty years while steadfastly focusing on the evolving needs of its consumers, across 110 countries globally. With exports counting for 90 per cent plus, of our production of dairy and meat products, an ability to stay ahead of evolving consumer trends, while also coping with volatility and disruption, has been a definitive requirement in sustaining the Irish Agri food sector.

The sector supports 220,000 real livelihoods and 800 real businesses, according to the CSO, that multi-annually supply millions of tonnes of food to 110 countries across the world.

Demand for Irish grass-based dairy and meat products is increasing. A continuing focus on improving the economic and environmental sustainability of this core aspect of the Irish national economy is critical to sustaining the economic and social relevance of the agri sector to the National Irish economy.

Moreover, focusing on low emissions efficiency is increasingly in tune with a global narrative that recognises the need for specialisation and balance in addressing the twin global challenges of emissions reduction and feeding a growing global population.

Magical thinking about a plant-based Nirvana won’t trump the core realities of basic economics and the ongoing refusal at EU and local Irish level to join up policy on regulating food production with food pricing.