Ciaran Fitzgerald

Agri-food economist

First, kill all the cows!

It’s difficult, verging on farcical at times, to witness how small-island-minded and self absorbed the public narrative around climate challenges and environmental impacts has become in Ireland.

Reducing cow numbers – culling, killing – whatever you want to call it, seems to be the solution put forward by various organisations and agencies. Whether it relates to meeting Ireland’s overall carbon-emissions reduction target or delivering on the Nitrates Directive.

The clarion call to cull cattle has become so encompassing, in terms of solving the ailments of the country that, at this rate, it may well become a solution to the delays and price escalations of the new children’s hospital. And why stop there? What about the failure since the mid-1950s to build a metro link between Dublin Airport and the city centre (despite spending €300m on consultants before any digging or tunnelling has taken place)? Reducing cattle numbers will surely sort that out. Right?

Food security

In the ‘real’ world the need to balance climate impacts with the equal imperative of meeting increasing global food demand is very much a key focus. Indeed, the Paris Agreement to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), adopted at the Conference of Parties (COP) 21 in 2015, specifically ‘recognises the fundamental priority of safeguarding food security’ and commits its members (including Ireland) to resolving to ‘foster climate resilience and low greenhouse gas emissions development in a manner that does not threaten food production’.

Moreover, and more recently, as an input to the recent COP 28 in December 2023, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), submitted a detailed and comprehensive report focussed on balancing the challenge of decarbonisation with the equal challenge of feeding a growing global population. The FAO report emphasised ‘improving animal health, adopting better breeding practices, and reducing food loss and waste while also focussing on emissions reduction’.

This contrasts greatly with the public narrative in Ireland – the food island – where the general theme revolves around culling cows.

Reality check

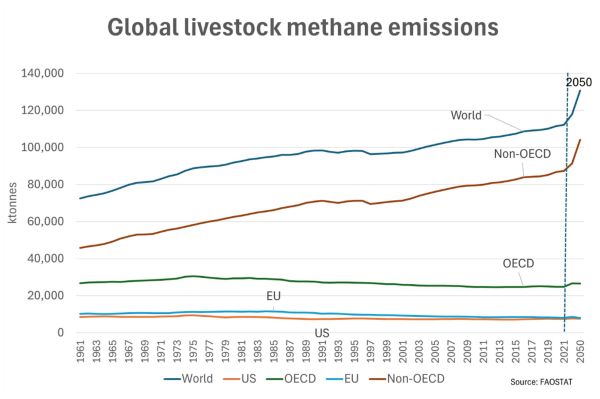

There is an entirely pragmatic basis for promoting this more balanced and constructive approach, in my view. It is most likely driven by the fact that, as per figure 1, while livestock emissions in the EU, US and other OECD ‘regulated’ countries are in decline, livestock emissions from ‘non-regulated’ regions are increasing. This reflects the reality that increasing global demand for meat and dairy will be met by unregulated regions. This is a lose-lose for global climate impacts, especially if the blind obsession with constraining output in Ireland and the EU continues.

What the Paris Agreement has not done, nor the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), nor any of the 28 COP iterations, is to declare dairy and meats as non-sustainable foods. They have also not suggested that plant-based foods are the only sustainable future food types. But you would be forgiven – in Ireland anyway – for thinking that the opposite is true.

But this does not reflect the balanced approach to climate challenges as set out in global agreements, nor does it stand up against nutritional science and dietary experts.

A sustainable model

Ninety per cent of our dairy and meat production is exported to 120 countries, globally. And there are many thousands of Irish people in Irish companies who, every day, engage with customers, worldwide and respond to evolving global demand for sustainable food. Their real-world competence and expertise are dismissed as ‘industry prejudice’ in this very shrill, tribal, binary diktat on food, agriculture, climate and environment.

In essence, much of the public debate in Ireland on global food challenges ignores industry competence and expertise in favour of local obsessions and prejudices. The full picture in terms of the critical balance between global food and global decarbonisation imperatives is dismissed or excluded while the proven realities of carbon leakage impacts are also dismissed.

And yet the people of Ireland are very aware of challenging debates in countries like Germany over the need to decarbonise that economy while sustaining a core car industry that still produces internal-combustion-engine cars, or the continuing importance of coal mining in Poland for its economy, energy security and employment, for instance.

It is about time, in my view, that the broader trade-off debates, and the embedded, very real, ‘practitioner’ competence in meeting global customer requirements, are properly included in the national debate in a balanced, constructive manner.

Realistic, constructive debate must replace the incestuous, small-island agenda that has demonised livestock farming through weaponising emissions-accounting protocols and has completely ignored the need for balance and global perspective.