Ciaran Fitzgerald

Agri-food economist

Irish beef – the optimal system

The industry in the 1990s and early 2000s was characterised by the export of frozen, commodity beef to North Africa and Middle East markets and, after the outbreak of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in 1996, frozen beef exports to Russia.

The real impact of BSE, despite a mistaken initial sense that it was a mainly UK phenomenon, was a huge challenge for all beef producers. It was particularly challenging for beef-exporting countries like Ireland, not least because a significant response to consumer concerns about BSE and beef, right across European markets, was a preference for locally produced product. In addition, many global customers also banned beef imports from the EU. For a country like Ireland, which exported 90 per cent of its production, this very clearly represented a huge challenge.

Consumer-facing reorientation

Nevertheless, in the post-BSE era, while also managing the decision by the EU – as part of a commitment to World Trade Organisation (WTO) deals – to phase out export refund subsidies, the Irish beef sector very quickly and very successfully developed a much more ‘direct-consumer-oriented’, largely fresh, beef-export business.

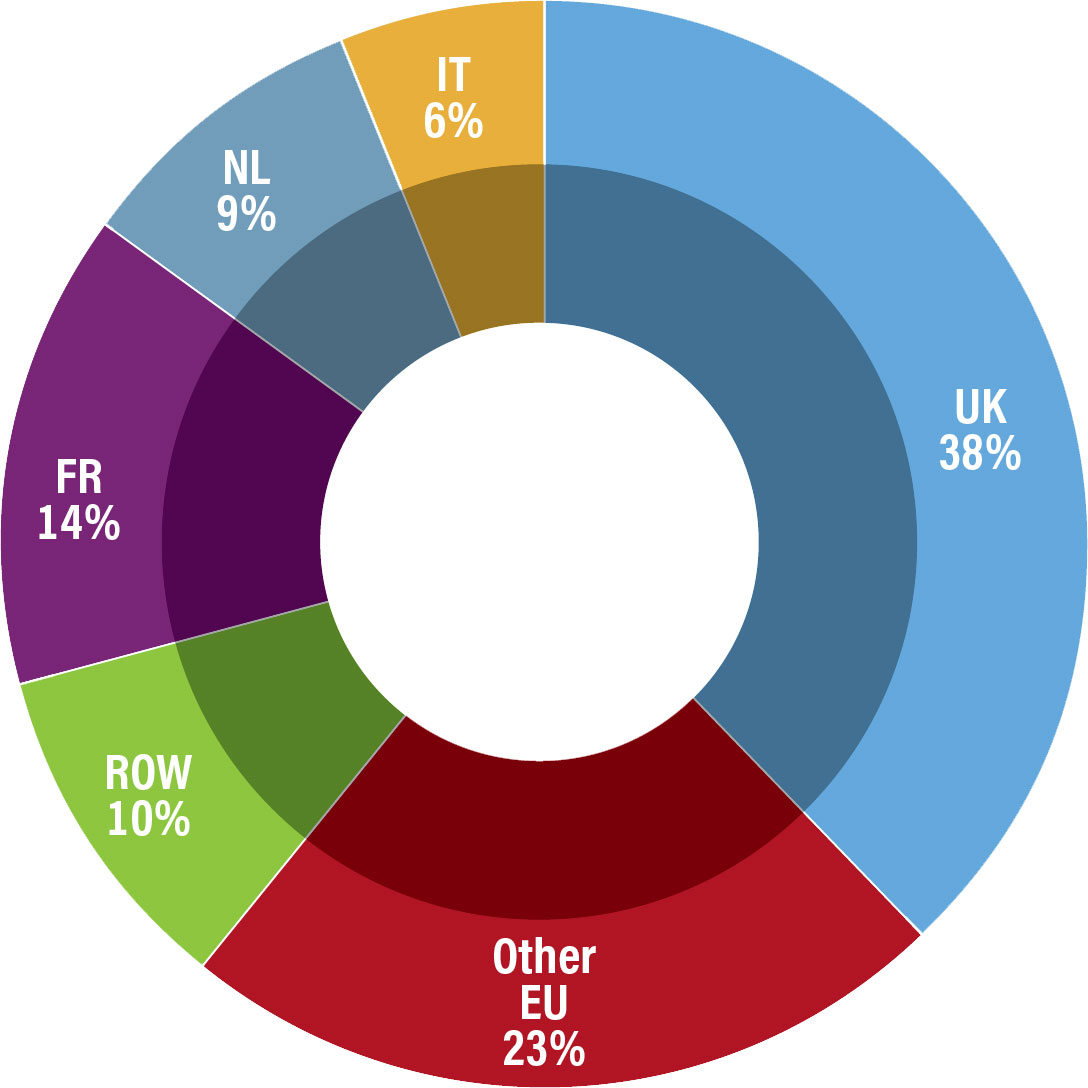

By 2023, with annual sales averaging around 600,000 tonnes, Irish beef exports were focused principally on the UK and the rest of the EU countries with world market exports accounting for less than 10 per cent of total output (Figure 1).

Moreover, having successfully adapted to the post-BSE world and the abolition of export subsidies, the Irish beef sector has also coped exceptionally well with the UK decision to exit the EU Single Market after the Brexit vote in 2016.

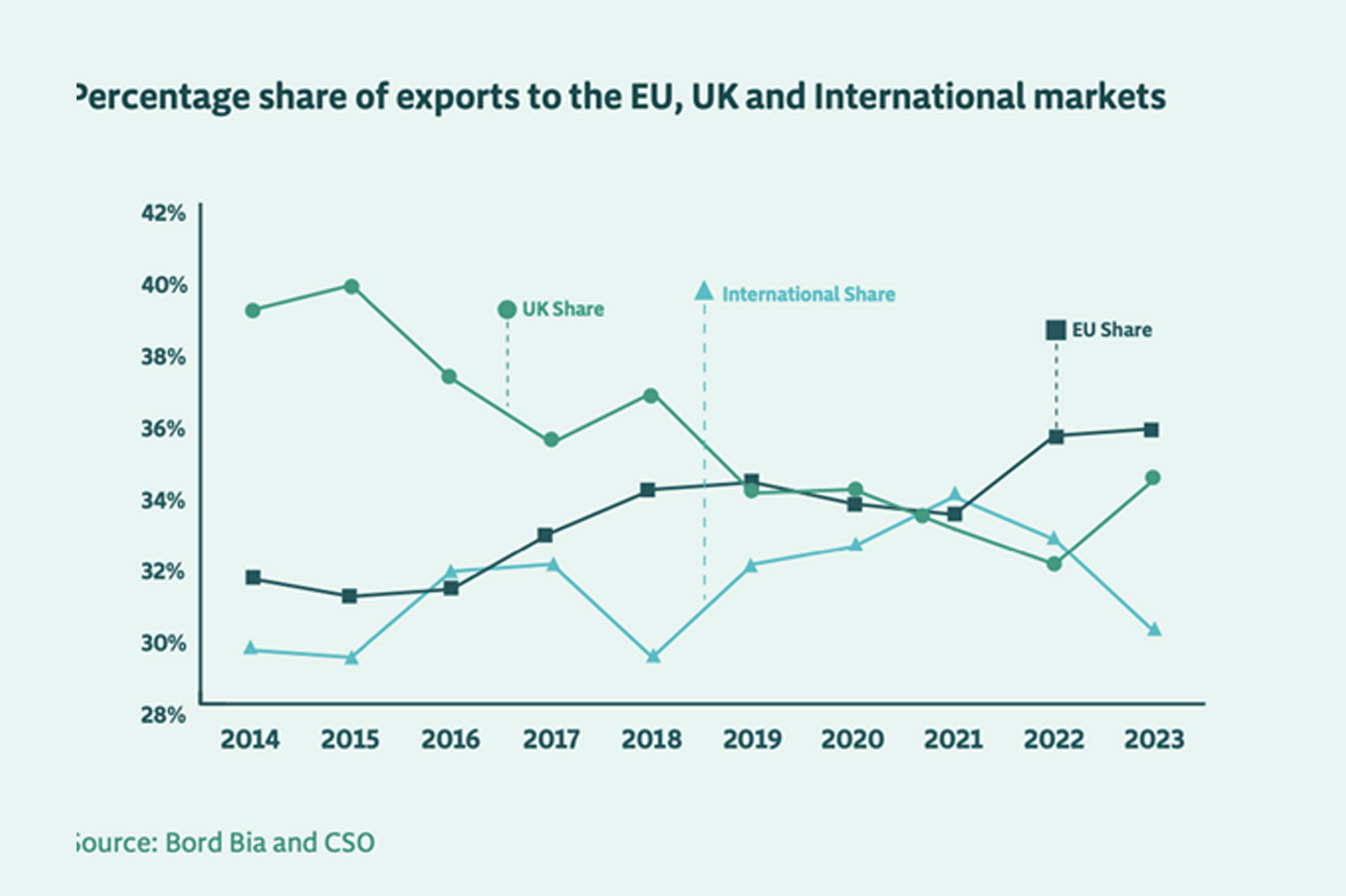

Figure 2 shows – as per Teagasc’s 2023 outlook report – out of a total export value of €2.7bn in 2023, the UK accounted for 34 per cent of Irish beef exports with other EU countries taking 36 per cent of the total.

Figure 1: Estimate of Irish beef export markets by volume in 2022.

Source: Eurostat COMEXT, January to August (2022), taken from Teagasc’s 2023 outlook report.

Demonisation of beef production

Climate-change challenges, both in terms of emissions from beef production and the large-scale promotion of artificial/lab-produced meat alternatives, have also impacted the beef sector.

As is the case with the Irish dairy sector, the public narrative of the last three years seems hell bent on demonising and reducing Irish beef output. This is in direct contrast to the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) thinking, which prioritises carbon-efficient production systems, and OECD/FAO and EU Commission-validated research, which highlights the consequences of the carbon leakage effect as a result of replacing Irish beef exports with beef produced in Brazil. Such consequences include twice the emissions and associated environmental destruction.

Beef cow numbers fall

The supply side of the Irish beef sector has also seen its fair share of change and adaptation. The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) Reforms of 1992 under Commissioner Ray McSharry created a direct-payment system across the beef production sectors and, in particular, provided direct-income supports for suckler-cow producers. As a result of the direct support, Irish beef cow numbers increased from 500,000 head in the late 1980s to 1.12 million head at peak in 2012.

As part of the 2000 CAP reform and, again, in response to WTO commitments, CAP direct payments were decoupled from production.

While France, Spain and Austria opted to keep a coupled payment for suckler cows, Ireland decided not to avail of this option. Teagasc/University of Missouri Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute (FAPRI) forecasts predicted at the time that decoupling would see a substantial fall in suckler-cow numbers. While this did not happen immediately, the impact of decoupling payments, combined with automatic reductions in supports due to CAP greening requirements, have resulted in a cumulative fall of 309,000 in beef cow numbers from their peak, a 27 per cent fall by December 2023.

This significant and continuing fall off in beef-suckler-cow numbers means that, for the processing sector, the bulk of future supply will have to come from the dairy herd, even as Central Statistics Office (CSO) figures indicate a levelling off in dairy-cow number as indicated by the December 2023 CSO livestock census figures.

Figure 2: Percentage share of exports to the EU, UK and international markets. Source: Bord Bia/CSO.

Increasing meat yields

The response to concerns about the meat-yield capability of animals coming from the dairy herd has led to significant investment in sexed semen to improve breeding accuracy for replacement heifers and improve the meat characteristics of other dairy progeny. Teagasc figures for 2024 show that use of sexed semen in dairy has doubled compared to the previous year. Meanwhile, the need to reduce emissions from the beef sector has also meant a commitment to earlier finishing of beef animals.

Joined at the hip

The Irish beef and dairy sectors are very much interdependent, with the ongoing decline in beef-cow numbers an increasing percentage of beef factory throughput will come from the dairy herd.

Crucially and very clearly, ‘if’ Ireland can manage the new Nitrates Derogation (a very big ‘if’), a competitive, efficient beef-processing sector will be required. This is especially important in the medium-term scenario given that exporting of live animals is likely to become more and more restrictive, if not banned altogether. In that scenario, processing throughput would need to increase substantially from its current levels.

Economic opportunity

The beef sector in Ireland has maintained its Irish economic impact over recent years and can even extend this impact into the near future as EU beef production in other member states declines and demand for Ireland’s grass-based beef offering is sustained.

As with the totality of the Irish agri-sector, much depends on aligning Irish national policy with the growing awareness globally. This means that a balanced approach to reducing agriculture-related emissions, while feeding an ever-expanding global population from carbon efficient countries like Ireland, is not just desirable, it is also optimal on so many levels.